Nice terrorist attack refocuses attention on the Sahel

Published on 2016 July 28, Thursday Back to articles

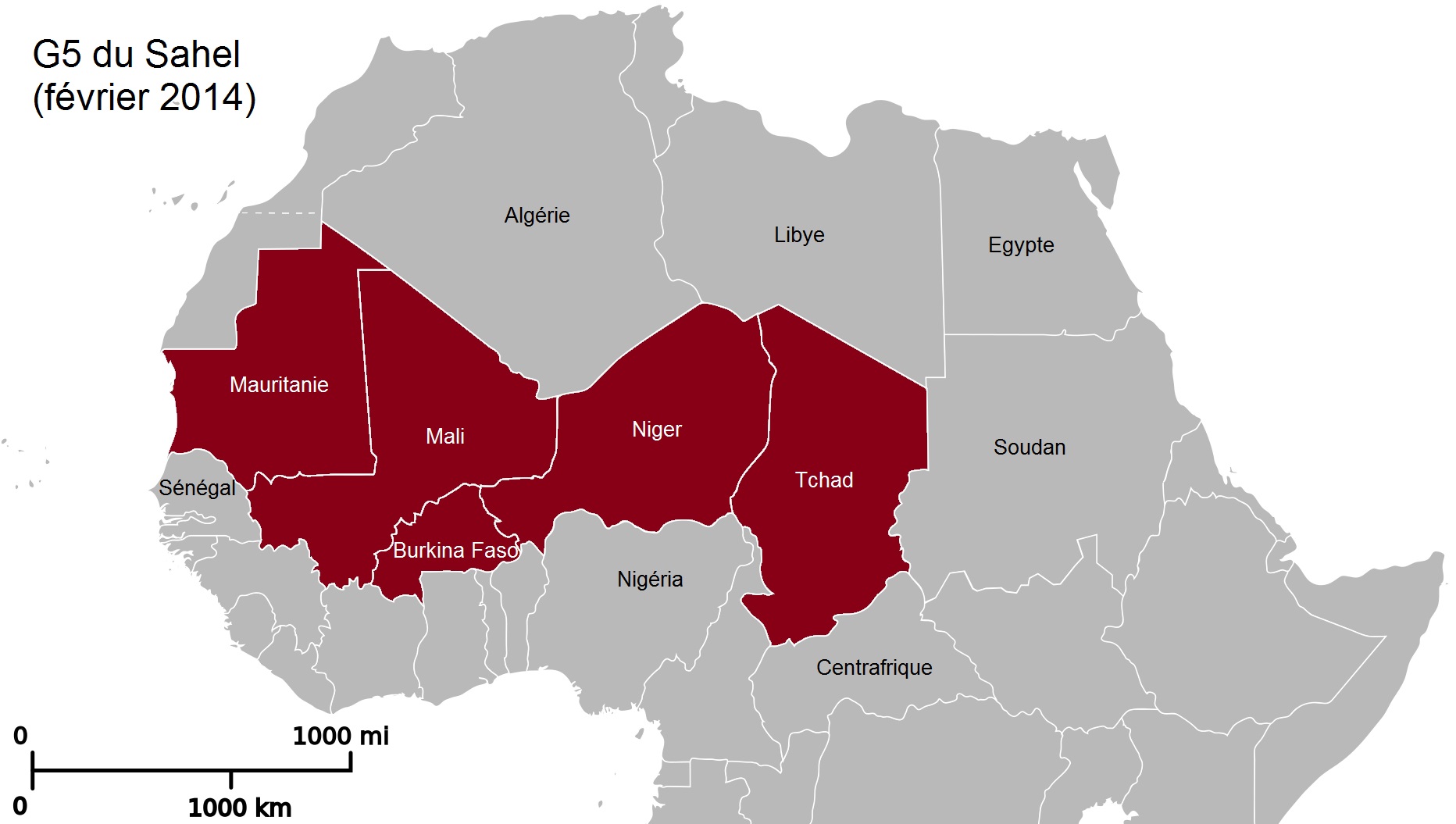

G5 Sahel Map (c) LeGrandJardin CC 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The terrorist attack in Nice, on Bastille Day (14 July), in which at least 84 people were killed and hundreds injured, has once again raised questions about what is going on in Africa’s Sahara–Sahel region.

Mohamed Lahouaiej Bouhlel, the driver of the truck that killed so many people, was a native Tunisian and a French resident, and the incident has not been linked definitely to the Islamic State (IS) group despite its claim. It is also unclear whether Bouhlel was a member of IS or perhaps recently radicalised or inspired by it. What is clear, however, is that France is a focus for a great deal of terrorism.

Writing for Middle East Eye on the day after the attack, Nafeez Ahmed explained, ‘The persistence with which France is being targeted can only be explained by the escalation of a secretive war with IS being carried out just across the Mediterranean in the Maghreb.’

He elaborated: ‘Over the past half decade, Islamist militant factions affiliated to both the Islamic State and al-Qa’ida have dramatically expanded their foothold in North Africa. Spurred by the vacuum left from the aborted NATO war on Libya, which successfully ousted deposed Muammar Qadhafi but left the country in a state of internecine civil war, Islamist groups have found a new base there.

‘Libya is now the perfect springboard for Islamist militants to expand their reach across North Africa and the Sahel. The result is patchwork of rapidly growing cells of jihadists loyal to multiple terrorist franchises: Ansar al-Shariah, al-Mourabitoun, Boko Haram, al-Qa’ida in the Maghreb, and Islamic State.’

The presence of IS and al-Qa’ida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) in North Africa and the Sahara–Sahel region is more complex and dates back longer than the above statement suggests.

The essence of Ahmed’s article is the same as that made by Sahara Focus in November 2015 in the wake of the 13 November Paris terrorist killings, and in February 2016 in the wake of the attacks on the Radisson Blu hotel in Bamako and the Hotel Splendid in Ouagadougou.

It is that France’s military intervention in the Sahel, starting in January 2013, along with its extensive support for the region’s many repressive regimes, stokes local grievances but does little to shut down terrorist networks.

As noted in Foreign Affairs by Nathaniel Powell, a specialist in the history of French military interventions, the French operation in the Sahel ‘may be doing more harm than good, since it provides crucial support to the repressive governments that are at the heart of the Sahel’s problems.’

In spite of the presence of at least 3,800 French troops across the Sahel, along with contingents of several hundred Dutch, Swedish, and German troops, aided by US specialists – not to mention the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilisation Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) force of 10,000 men – radical violent extremism had taken a deeper hold.

The prolonged French military presence is without doubt providing jihadists with a strong ideological weapon, not just in the Sahel but against the West in general. France is being portrayed as the infidel that must be attacked and removed from the region. In that sense alone, the French presence appears to be exacerbating rather than diminishing extremist militancy in both the region and mainland France.

Sahel on West’s agenda

International organisations and agencies such as the EU, UN, the African Union (AU), the World Bank (WB), and the African Development Bank (AfDB), as well as many individual countries such as the UK, had all placed the Sahel towards or at the top of their agenda even before the Nice attack.

For example, on 17 June, Federica Mogherini, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and Vice-President of the European Commission, met with Mohamed Tahar Siala, Moussa Faki Mahamat, and Ibrahim Yacouba, the foreign ministers of Libya, Chad, and Niger respectively, to discuss the best way to promote secure borders between their countries.

For the EU, the key challenges facing these borders are terrorism, arms smuggling, human trafficking, migrant smuggling, and irregular migration. Mogherini also hosted the foreign ministers of the G5 Sahel (Chad, Mali, Burkina Faso, Mauritania, and Niger) at an EU-G5 ministerial meeting in Brussels. The five main issues under discussion were as follows:

> implementation of the Malian peace agreement

> control and management of Libya’s southern borders (in terms of security and migration flows)

> countering terrorism in the Sahel

> all aspects of migration in the Sahel

> development, especially the creation of jobs and opportunities for young people.

A trust fund amounting to over €500 million (US$551 million) had already been approved for the countries of the Sahel and Lake Chad at the Valletta Conference in November 2015. A further meeting to strengthen the security and defence capacities of Chad, Burkina Faso, and Mauritania was held in Luxembourg on 28 June.

A Sahel for everyone

The main problem in countering terrorism in the Sahel is the cacophony of international organisations. To use the old English proverb, ‘Too many cooks spoil the broth.’ There is hardly an international organisation or agency that does not have its own mission in the Sahel, not to mention several Western countries acting on their own initiative.

Several countries have national plans for the Sahel. France has taken the lead with Operation Barkhane, while Spain, the Netherlands, Germany, and possibly now also the UK have been developing policies for assistance to the Sahel countries.

Some of these strategies are being implemented directly by special envoys based in Dakar and Bamako. For example, since 2014, Ethiopia’s Hiroute Guebre Sellassie has undertaken the functions of UN special envoy for the Sahel alongside Spain’s Angel Losada, commissioned by the EU, and Ambassador Jean-Daniel Bieler, Switzerland’s special envoy for the region, who combines his responsibilities with the states of Africa’s Great Lakes region (Burundi, Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda).

Another individual with similar functions is Pierre Buyoya, former president of Burundi and now acting as the AU’s top special representative for Mali and the Sahel.

In addition to these special representatives are dozens of international NGOs, special military missions and advisers, and a seemingly ever-expanding diplomatic corps respecting countries that only a few years ago had no representation in the region at all.

The outcome is a chaotic and burgeoning foreign mission industry that thrives by providing rented luxury offices, staff, fleets of 4x4s, and all the other accoutrements that accompany such a massive international presence. The funding of this international lifestyle comes from the envelopes intended to support the resilient populations of the Sahel against terrorism, associated domestic conflict, and poverty.

There is little coordination between so-called partners. More often competition, duplication, and even triplication are the order of the day, with being accomplished as fashion dictates whether it is climatic change, gender equality, terrorism that tops the bill.

At a joint conference in November 2013, UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, African Union Commission president Nkosazana DlaminiZuma, European Commissioner for Development Andris Piebalgs, World Bank president Jim Yong Kim, and the then president of the African Development Bank, Donald Kaberuka, all swore that individual work would give way to cooperation, coordination, and the simplification of fund disbursement procedures.

Sadly for the people of the Sahel, there has been little sign of any of these things.