How Buhari’s sick leave could change security and the naira policy

Published on 2017 February 23, Thursday Back to articles‘Anyone who tells you they know how sick Buhari is and when he’s coming back is lying,’ said a senior Nigerian official passing through London. He was responding to mounting speculation about what ails President Muhammadu Buhari, how serious the illness, and whether he may be about to retire from the presidency. At the last count, Buhari was said to have been suffering from one or several of the following: Alzheimer’s disease, pancreatic or prostate cancer, or Ménière’s disease. Are they all lying?

The senior official, who saw Buhari this week as part of a stage-managed visit by Senate president Bukola Saraki, told Nigeria Focus there would be no early resolution of the health crisis: ‘I think the earliest we will see President Buhari in Abuja is late March. Although we were not privy to all the medical details, it is evident that he has to rest and cannot resume the burden of the presidency immediately.’

Although the official’s explanation was careful, he suggested that Buhari was not being well served by his inner circle – his uncle Mamman Daura, Chief of Staff Abba Kyari, and Secretary to the Government of the Federation (SGF) Babachir Lawal.

‘They have controlled information to a paranoid extent, and created more worry than was absolutely necessary,’ he said. ‘Nigerians are hugely sceptical about all government announcements, so there has been a feeding frenzy … All this is in a country that can be said to have invented fake news.’

The other effect the official identified is a new political dynamic in the country. During Buhari’s prolonged absence, there have been signs of shifts on two big issues: a deal with communities and militant groups in the Niger Delta to get guarantees on oil production security; and a concerted push against Central Bank governor Godwin Emefiele’s strictures on the exchange rate.

These shifts reflect wider political differences within the government. Generally, Buhari, Kyari, and Emefiele strongly oppose more flexibility on the exchange rate, let alone a full-bore devaluation. But Vice-President Yemi Osinbajo – who has had full powers as acting president since 19 January – favours ‘a convergence of the two exchange rates as soon as possible,’ as he now publicly says.

In practical financial terms, that can only mean a substantial devaluation of the naira’s official rate from its current peg of ₦315/US$ to something approaching the parallel rate, which is now south of ₦500/US$.

And it is not only Osinbajo who holds that view.

It is the entire economic team that he is meant to be running: Finance Minister Kemi Adeosun, Budget Minister Udo Udoma, and International Trade and Investment Minister Okechukwu Enelemah, and Deputy Petroleum Minister Emmanuel Kachikwu.

All those ministers are technocrats, but they have the support of other, more politically minded ministers such as Power and Works Minister Babatunde Fashola and Mines Minister Kayode Fayemi. This gives the forex reform lobby much greater weight in the government now. The calculus is that the longer Buhari stays in London – whatever the nature of his ailments – the more likely the government is to move towards further devaluation.

Foreign exchange traders already see signs of currency bets in favour of devaluation. Yet the naira policy remains extremely delicate for Osinbajo, who is a technocrat par excellence, leading a group of other technocrats. The vice-president has no independent political base but owes his position almost entirely to Lagos State’s former governor, Bola Tinubu, who is the political godfather in the south-west.

Given Tinubu’s role in co-founding the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC) with Buhari, he was entitled to nominate the running mate. He picked Osinbajo, who had been his attorney general in the Lagos State government, with the hope of retaining influence over government appointments and naira policy.

Although Osinbajo has proved more independent than Tinubu might have liked, he hasn’t severed all ties.

Kaduna State governor Nasir el-Rufai told Nigeria Focus that Buhari regarded Tinubu as a ‘semi-detached member’ of the APC and that this would have wider implications for the government. Recently, there has been speculation that Tinubu and former vice-president Atiku Abubakar (1999–2007) are teaming up to challenge Buhari for the presidency in 2019.

Buhari’s sickness has, it seems, forced everyone to recalibrate their tactics. But the Tinubu– Buhari fault lines remain. For example, Kyari and Emefiele suspect that Tinubu was behind the May 2016 decision – reached by Osinbajo and Kachikwu – to deregulate imported fuel prices.

The decision was made during another of Buhari’s absences. It also forced Emefiele’s hand on the exchange rate: he had to withdraw the currency peg – at ₦197–99 to the dollar – on the official exchange rate. Since then it has depreciated by about 40%.

In recent weeks, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) website has been carrying critiques of saboteurs and ‘so-called reformists’ who are trying to weaken the currency. That suggests Emefiele wants to fight back hard, and that he thinks he will have the full backing of Buhari and Kyari to do so.

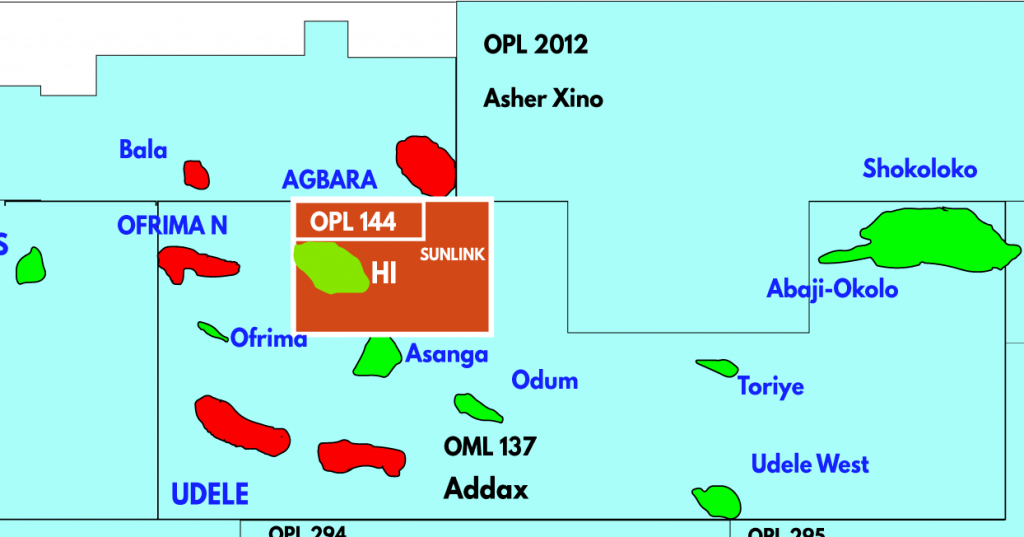

Similar divisions have emerged over a deal in the Niger Delta, with Osinbajo and Kachikwu taking a more pragmatic stance.

They are willing to parcel out oil-lifting contracts to companies linked to prominent Delta business and politicians, and are also finding a way to license many of the illegal small refineries in the region. The military is currently forcibly closing down these refineries and arresting the operators, which is causing increasing resentment.

This is where some of the security and naira policy divisions could start to have implications for political stability, according to National Security Adviser General Babagana Monguno: ‘There are fissures in both the big parties – APC and [Peoples Democratic Party] PDP – and people are using these security and naira policy issues, which have their own financial implications, to divide the parties further.’

Some of Monguno’s colleagues point out that many politicians in the Niger Delta would stand to gain from a more pragmatic policy towards militants and illegal refineries, although it would also help boost national oil production.

Similarly, they say some business interests stood to gain from a sharp devaluation of the naira ‘There’s a lot of plotting going on at the moment,’ said Monguno, ‘and that’s not good for naira policy continuity or for resolving the big economic issues.’

He was much more upbeat, however, about the government’s campaign against Boko Haram in the north-east, which has been strengthened by international co-operation. Having attended an international security forum in Munich, Monguno said there was a far greater international awareness of the complexity of the Boko Haram and allied threats in the region.